“It’s OK not to be OK”: fashionpreneur George Hodgson, 25, on mental health

- Leah Jewett

- May 27, 2021

- 9 min read

He’d been hyperactive and anxious as a child, but it was taking ecstasy at age 16 that spiralled George Hodgson into panic attacks and OCD (obsessive compulsive disorder). Living at home and doing therapy, he turned to drawing and writing as an outlet for his feelings. Then, at age 22, he transferred his ideas onto T-shirts and hoodies designed to start conversations about mental health and, printing them on his family’s kitchen table, launched Maison de Choup (Choup was his nickname for his sister Charlotte) – tagline: Making Mental Health Matter. It was dubbed by Vanity Fair a “fashion brand with a mental health cause at its heart”. In 2019 George appeared in the BBC series Amazing Humans in the 4-minute video The designer using fashion to raise mental health awareness. Now 25, George speaks in schools, colleges and workplaces and works for the young people’s mental-health charity YoungMinds, donating 25% of the profits from some T-shirt designs to them.

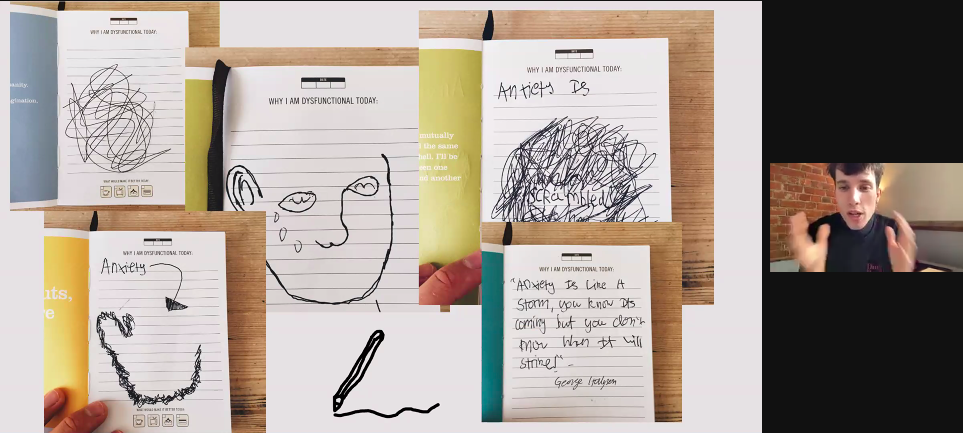

We were moved by watching his Managing Stress And Anxiety talk this April during the Speakers Charter’s Back To School Mental Health Refresher and impressed by how George draws on his own struggles to reach out to others.

Here George tells us how his mental-health issues affected his family, how parents can get their child to talk openly and how clothes can spark conversation by design

In primary school I was anxious, always on the go, always fidgeting. At secondary school my hyperactivity seemed to die down, probably because I was putting all that energy into studying and being sociable.

Then doing ecstasy with friends at a festival was the catalyst that brought back my severe anxiety. Weeks afterwards I had what I later learned was a panic attack. I’d convinced myself there were still drugs in my system. I was in a really low place.

When I was told I’d have to wait 40 weeks to see a doctor on the NHS, I didn’t know if I would still be there. It was scary. Fortunately my parents could afford to get help privately, so for 18 months I did hypnotherapy with a psychiatrist then did CBT (cognitive behavioural therapy) with a psychotherapist for another 18 months to get through the OCD and anxiety.

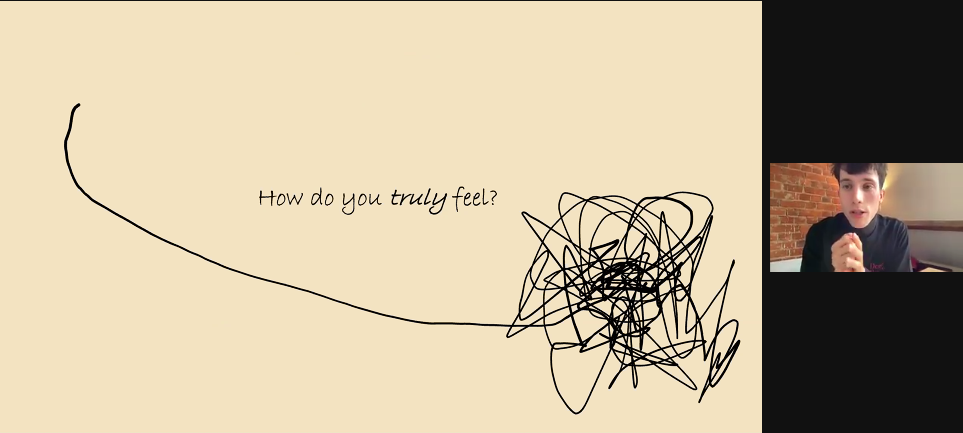

During this time, when I was very isolated, I used to write down and draw my feelings in these little notebooks and I thought: “If I can put my designs on a T-shirt, then I can talk about my mental health to my uncle and cousins and say: This is about what I’m going through” in a way that didn’t explicitly involve me saying: “Sorry, I can’t talk to you – I’m experiencing some anxiety at the moment.”

Wearing his art on his sleeve: George Hodgson speaking during the Mental Health Refresher

Coming out of the three years of help I realised: “What on earth do young people do who can’t afford to go private? That’s a terrifying thought.” Then it became more about helping young people and their parents who maybe were going through the same thing.

Now I’ve got my anxiety under control and I know what my triggers are, what will make me feel uneasy. I’ve still got bounds of energy and I’m still fiddling, getting bored, losing interest quickly and thinking: “When’s the next thing coming?”

But that almost helps with having a business and trying to get opportunities – I don’t see it as a bad thing, because it turns into tenacity.

On how a child’s mental-health issues can affect their family

When I was really young I didn’t think much about being hyperactive. I just thought I was quite energetic. My parents got someone to come to the house to give me extra support and kind of calm my personality down a little. So I had breathing exercises and counting to 10, which was helpful at school.

Then when I suffered really badly at 16 my parents were very supportive. They didn’t understand then, nor did I, but they learned along with me. The psychiatrist was teaching them how to look after and manage me. The bottom line was: “Don’t tread on eggshells. Don’t treat him like there’s something wrong with him.” Because then I’d start worrying. I knew there was something wrong with me but I didn’t want people treating me differently. I just wanted it to be normal. I wanted to feel normal. I wanted to feel like I was getting better.

When I was at rock bottom, my mental-health issues almost tore the family apart. I was controlling the environment. Because of my OCD I was washing my hands all the time and going through loads of soap; the towels were always wet. That was exhausting. Also I was having panic attacks and couldn’t go anywhere without my parents. It was hard work.

I could see that it was difficult – I just couldn’t do anything about it. And I felt kind of powerless, which made me feel not necessarily terrible but just aware that I didn’t get better. It was quite scary and sad to see.

But if I had a bad day, my mum and dad were there to talk, and my sister sometimes on the phone. I’m very lucky that I’ve got a close family unit. That was a major part of my recovery.

On the fashion label that names or labels mental-health issues

I’m a mental-health campaigner – I’m campaigning through fashion, so I suppose I am in a way a fashionpreneur. I’m also studying to become a psychotherapeutic counsellor.

I wonder if there’s a difference between label and a name. At first I didn’t know what a panic attack was – I thought I was going mad. It was terrifying. For a lot of people, if they don’t know what they’re feeling, it gives them clarity to give it a name. Having my issues identified helped me to recognise that there was actually something going on. I could say: “Oh, I’m suffering from anxiety. This is why, and this is what I’m feeling.” That made it manageable.

Maison de Choup is a fashion brand slash label – but it’s about designs that are subtle and non triggering and they never label anything. You’ll never know what the design is about if you don’t ask. That’s important, I think, because you never know what someone’s going through. The designs are meant to be almost obscure, so that someone says: “What does that mean?” It’s starting that conversation about mental-health problems.

The hardest part of suffering from poor mental health is opening up about it, so having a product which does that for you is important. You could say: “I bought it because I experienced something in the past” or: “Actually I’m going through something right now.” But you don’t even have to speak about yourself – you can say: “It’s from this brand that’s raising awareness about mental health. It was started by this guy who suffered himself.” You’re talking about mental health, and that’s the brand’s mission. It’s the conversation-starting element of the product which we’re all about.

Now more than ever it’s important, I think, to have meaning behind things. We see fashion brands that are so fast – people buy clothes then throw them away. For what reason? It’s so weird to me. I think that whatever you do in life – whether it’s big or small – should have some form of meaning. If you don’t enjoy it or it’s not giving you meaningful value or purpose, explore something else. With the brand, everything we do is for a reason. It’s to change the way we talk about mental health; it’s to make mental health matter.

On supporting parents to support a child with mental-health issues

If a parent is in desperate need of knowing what to do, the YoungMinds parents’ helpline can guide them.

It’s important that there is some sort of knowledge that helps parents to understand what their child is going through and how to manage it. Parents don’t necessarily need to be involved. It’s one of the most difficult things to hear as a parent, but when your child is ready to talk to you, they will. So I think parents should give their child the space to talk when they feel comfortable and not ask: “What are you going through?” over and over. If you say to your child: “Whatever you’re going through, I’m here if you need to talk, whenever you feel ready” you’re giving them that open door and saying: “I’m always here for you” in a way that maybe doesn’t make them feel like they’re being suffocated.

I think it can sometimes make it more difficult if you try to intervene too much. My parents didn’t interfere until I needed it. If I was having a panic attack or crying, I could go to them. They obviously had some sort of knowledge from the psychiatrist, which helped. It gave me relief to think: “I’m feeling through this, but if I need to speak to someone, I know who I can go to first and foremost.” I felt that safety. For young people, it’s not always their parents. It might be a friend or a loved one.

Some people just need someone to listen to what they’re going through – or as we like to say in our family, to dump on – sometimes without saying anything. But it’s important to check in on a person if you’re about to dump on them because it can be emotionally heavy.

In terms of encouraging a child to talk who doesn’t want to, I can only speak from lived experience. Maybe open the door in ways that might not seem obvious. Send your child a message or a quote about mental health – something not damaging but relatable or uplifting – so you’re kind of on the same level as them, you’re understanding what all people experience, not just your child. You know: “I saw this, thought of you, thought it would be important for you to see.” Your child might not reply, but it’s just kind of showing them that you understand and you’re not pressuring them to do anything at the moment. The most important thing is encouraging your child that you’re there for them if they need a conversation, not forcing it. I’m a firm believer that when they’re ready, they will talk to you.

On how mental-health topics are off limits for boys and men

Once I did a speech about mental health at an all-boys’ school, and there was only one question: “Did you get in trouble for taking drugs?” Afterwards I said to the head master: “Was that OK? Why were there no questions?” He said that they were listening and they were all engaged, they just didn’t know what to ask or how to ask in front of their friends.

Young men don’t know how to ask for help or ask questions about mental health because they struggle to “present”. They say: “Women and girls have more feelings; they’re open books in some ways.” Men bottle it up, which is not necessarily to hide – but because they don’t know how to approach the situation they throw it to the back of their mind and forget about it. Having a man speak about mental health shows other men that it’s OK – but it is a tricky one. I’m trying to encourage young men by saying: “Don’t feel ashamed to open up.”

The amount of messages I got privately after that school speech was huge! That’s the thing: boys want to open up, they just don’t know how. I get lots of messages from men, so it’s about my saying: “It’s OK. I’ve been through the same thing. I’m always here if you need to talk.” It’s baby steps.

On parents talking openly with their child about sex and relationships

School doesn’t teach enough about sex. It’s important to be honest and transparent. It’s probably the most awkward thing that can be brought up but it’s just more comfortable if it’s spoken about. Talking about it makes it less taboo. So if there’s a problem your child can go to you as opposed to going to Google. Just say: “Whatever you’re doing, I’m here if you need to chat or need any advice. Just be safe, look after yourself and make sure you check in, if not with me, with friends.” I can’t remember how we did it, but I know I can speak to my parents if something’s wrong. Having that home base is important, that space to be able to talk if you need to as opposed to hiding anything or going through it by yourself.

On campaigning via conversation-starting clothes

I used to have a market stall, and when I told people about the story behind Maison de Choup they were almost speechless. One person said: “The brand saved my life” because of the designs and speaking about mental health in a way that’s subtle but makes everyone feel related to it. It’s humbling, really, that people are out wearing the T-shirts and talking about the brand and subsequently talking about mental health. It makes me feel emotional.

It’s OK to open up about your mental health. In fact, it’s healthy. It was the saving grace for me. When you talk about it, you almost alleviate some of the thoughts inside your head because they’re so stuck there and you’re so absolutely paranoid about telling someone that they sort of manifest themselves. So being able to say: “I’m experiencing this” is almost a weight off your shoulders. Understanding that you’re going through something, and accepting it, will be the most important part of the recovery.

When I was better I thought: “I’ve got to share this message to help other young people.” So the mission was set out. In the future the brand will be a platform for young people to share their creative work and tell their stories. For now I keep campaigning, working for YoungMinds and running Maison de Choup to encourage as many young people, teachers and parents as possible that it’s good to open up and talk about mental health. There’s nothing to be ashamed of if you’re suffering. It’s OK not to be OK.

Read more about George here. Find him on Instagram and Twitter. Go to Maison de Choup

Comments